Saving Africa's mothers:

:

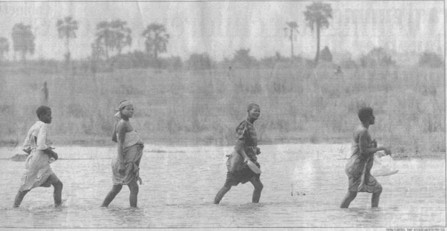

* Photo: Ben Curtis, The Associated Press / An African

woman has a lifetime risk of one in 16 of dying from pregnancy-related

complications. In the industrialized world, that number is one in 4,000.

Saving Africa's mothers: From

the time you've had your morning coffee until the same time tomorrow,

1,600 women will have died from complications of pregnancy and childbirth.

Monday, October 25, 2004

Page: A1 / FRONT

Section: News

Byline: Shelley Page

Column: Shelley Page

Source: The Ottawa Citizen (www.ottawacitizen.com)

Series: Birth of a Crisis (Contraception)

The men who brought in the pregnant mother claimed she had gone into labour 12 hours earlier. But Dr. Jean Chamberlain suspected otherwise. She had learned during her time in Africa that 12 hours usually meant two sunsets had passed.

Dr. Chamberlain looked at the woman. Her chart said she was 24, but she looked more like 17. Dr. Chamberlain hoped it would be a routine delivery and continued on her rounds.

A few minutes later, she was called back. The woman was having seizures that could harm the baby. There were no anti-seizure drugs available in the hospital. As they scrambled to prepare the operating room for a caesarean section, the seizures continued.

When the baby's misshapen head emerged, Dr. Chamberlain understood.

In fact, the mother had been in labour for several days. She quickly passed the newborn to the midwife, but there were no cries. The baby, a boy, was dead.

Dr. Chamberlain keened for the young woman. "Not only would she suffer grief, but also the ridicule that is often heaped on African women who experience an unsuccessful pregnancy." But at least her life had been saved. If she'd stayed in her village to deliver, she too, would be dead.

Dr. Chamberlain, of McMaster University, has emerged as one of the world's leading champions of women's reproductive rights.

She is executive director of Save the Mothers, and has founded a masters program in Uganda to train medical professionals across Africa on how to deliver babies safely.

During an interview, she rhymed off statistics that are almost impossible for the western world to fathom. From the time you have had your morning coffee until that same time tomorrow, 1,600 women will have died from complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Ninety per cent lived in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

This means an African woman has a lifetime risk of one in 16 of dying from pregnancy-related complications. In the industrialized world, that number is one in 4,000.

"Incredibly, in the 20th century, this stubborn scourge killed more than tuberculosis, suicide, traffic accidents, and AIDS combined. More women died from childbirth complications than the number of men killed in both world wars," she wrote in Where Have All The Mothers Gone?, in which she exposes the stories of pregnant women she met while delivering babies in Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Pakistan, Ecuador and Yemen.

Mothers in the developing world are dying. There are 529,000 unnecessary deaths each year, most of them in developing countries and many of them leaving behind a family of orphans.

Most of the deaths -- about 60 per cent -- are due to severe bleeding during unsafe deliveries, in large part because half of all women give birth without a trained attendant. The other 40 per cent are due to the consequences of unsafe abortion.

Recently, Ahmed Obaid Thoraya, the executive director of the United Nations population fund (UNFPA), spoke of the tragedy of maternal mortality.

"Maternal mortality is a crisis that does not get the attention it deserves. No other health indicator shows such a glaring gap between rich and poor nations," she said.

She said the developed world "knows how to reduce deaths": Expand access to skilled attendance at delivery, emergency obstetric care, and referral and transport services so that women can receive medical care quickly.

More than 80 per cent of developing countries say that available resources do not meet their reproductive health needs, she said, yet donor countries have given only about half the amount that they agreed would be needed to implement the Program of Action -- $3.1 billion U.S. a year rather than the $6.1 billion a year by 2005 that was pledged in 2001.

Dr. Chamberlain says, in addition to the many orphans, many of the mothers who survive have a fistula, a torn birth canal that leaves them incontinent: "Women who will be thrown out of their families and villages, like lepers" as a result.

Drugs that treat hemorrhages cost less than a cup of coffee. Infection and high-blood pressure -- other common causes of maternal death -- are also preventable. A majority of African women give birth without skilled attendants, either because they live far from clinics or because they can't afford them.

In Kenya, the exact number of women who die from pregnancy-related causes is unknown. Dr. Solomon Orero, a leading Kenyan expert on maternal mortality, estimates a very high 1,000 deaths for every 100,000 births. A more conservative government survey puts the figure at 590 deaths for every 100,00 births, up from 540 in 1998. With so many women living in rural areas, and so much shame surrounding these deaths, it's difficult to ascertain the real number.

Maternal mortality is increasing in Kenya because the country lacks the necessary health infrastructure and financial resources. At the same time, not everyone has access to, or believes in, contraceptive use. Contraceptive use has stagnated at 1998 levels. A recent study showed that one-quarter of babies were unwanted.

Beatrice Mutali, of International Planned Parenthood (IPPF)Africa, says it is working hard to establish "safe motherhood programs" across the country and help train birth attendants.

They are also trying to curb unwanted pregnancies.

"Africa has the lowest rates of contraceptive use in the world. Thirteen per cent," says Dr. Nememiah Kimathi, also if IPPF. He said that to encourage contraception, particularly condoms, is to change a society where men traditionally don't use them.

Ms. Mutali, director of programs for IPPF Africa, says they creating programs and "male-only clinics" to involve men in sexual health. They are also establishing youth programs to educate about sexuality.

The country is also in the grips of an illegal abortion epidemic. Abortion is only legal in Kenya if the mother's health is in jeopardy. There are an estimated 300,000 illegal abortions every year and about 5,000 women die annually from botched terminations. Sixty per cent of the women in the country's gynecological wards suffer from the consequences of unsafe abortion.

This May, Dr. John Nyamu and two of his nurses were charged with murder after being linked to the deaths of 15 fetuses dumped in a river in Nairobi. Documents found with the bodies linked them to the crime.

Dr. Orero, who champions women's rights to family planning and safe abortion, said he believes Dr. Nyamu, a friend, was framed in order to discredit the abortion-rights movement that is gaining momentum in Kenya.

"For us, it is the entire medical profession on trial," he said in an interview.

Dr. Orero led a delegation of doctors to speak to the country's attorney general on behalf of Dr. Nyamu, hoping to bring the issues of maternal mortality and unsafe abortions "into the open."

Kenya's abortion law is a vestige of the colonial era. It was established in 1861, when the country was ruled by the British. The British legalized abortion in 1967 although the law remains on the books in Kenya. This is the case in virtually every African country, except South Africa, which has abortion on demand up to 12 weeks. Numerous studies have shown that countries with the most restrictive abortion laws have the highest maternal mortality rates.

"We are saddled by the laws of our colonial masters," added Dr. Kimathi. "It's made abortion clandestine and illegal. The consequences and magnitude is huge."

Dr. Orero has treated thousands of women during the past two decades who have suffered the consequences of unsafe abortions. One of his first patients was a nursing student who was admitted, near death, with infection. She only admitted the abortion when she knew she was dying because she didn't want to face the shame of her act or to be expelled from nursing school.

Dr. Orero has repaired ripped rectums, bleeding stomachs, and removed rusty wires and coat hangers from the innards of his patients. Others are admitted after swallowing poison or fistfuls of malaria pills.

He works around the edges of the law, saving the lives of women who have already attempted to end their own pregnancy, using a procedure called manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), a simple method of abortion that did not require surgery or electricity. With an MVA kit, doctors can treat incomplete abortions, reducing the risk of infection and eliminating the need for surgery.

In the district hospital in Kisuma, the third largest city in Kenya, there has not been a death from unsafe abortion in three years. Before that, there were several every week.

K-MET, the organization of health care providers and counsellors he co-founded and heads, has created a network to train nurses and doctors to treat unsafe abortions. He travels throughout Africa, teaching doctors how to complete botched abortions.

Dr. Orero also exploits a loophole in Kenya's law, which allows him to legally end a pregnancy if the procedure is aimed at "the preservation of the mother's life" and if it is performed "in good faith and with reasonable care and skill."

Dr. Orero says that he is saving a woman's life if he ends a pregnancy she planned on ending herself with a more dangerous method. But even he admits that this a convoluted way to go about it. "If abortions were done legally, they would be "done without loss of life or shame. We could smoke out charlatans and incompetents."

Birth of a Crisis

The Canadian Conference on International Health begins in Ottawa on Sunday at the Crowne Plaza Hotel. See the Canadian Society for International Health website (www.cshi.org) for details. The conference includes discussions on maternal mortality, the impact of the U.S. global gag rule, and the worldwide contraceptive shortage.

Illustration:

* Photo: Ben Curtis, The Associated Press / An African woman has a lifetime

risk of one in 16 of dying from pregnancy-related complications. In the

industrialized world, that number is one in 4,000.

* Photo: The Canadian Press / Dr. Jean Chamberlain of McMaster University

is executive director of Save the Mothers and has started a program in

Uganda to train medical professionals across Africa to deliver babies

safely. She has delivered babies in Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Pakistan

and Yemen, and recounts her experiences in Where Have All The Mothers

Gone?

Idnumber: 200410250127

Edition: Final

Story Type: Column; Special Report; Series

Note: Ran with fact box "Birth of a crisis", which has been

appended to the story.

Length: 1597 words

Illustration Type: Black & White Photo